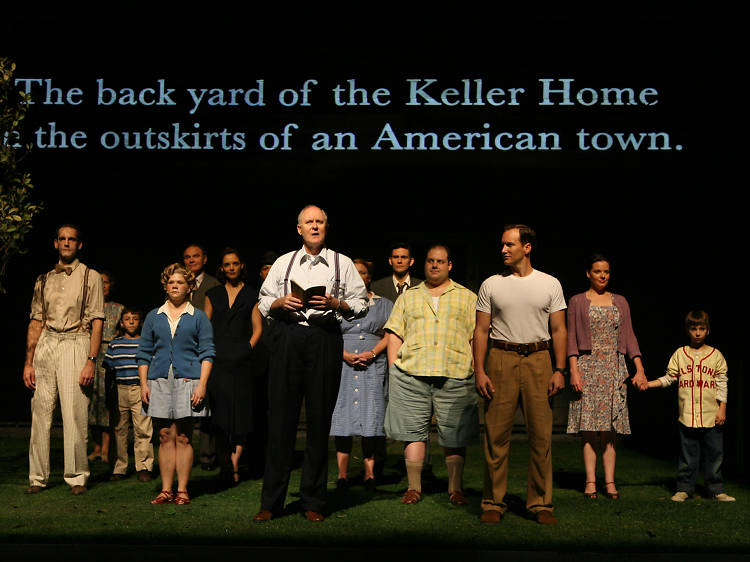

Lear

Young Jean Lee trampolines her devastating postdramatic construction off Shakespeare’s ultimate tragedy, King Lear, using the Elizabethan text to launch her own excruciating deconstruction of grief. Playful and biting, Goneril, Regan and Cordelia snipe at one another; sulky and competitive, Edgar and Edmund mope. Lee’s mean-girl courtiers suddenly give way, though, to women tortured by an inability to sufficiently love their parent, and the fourth wall tinkles into dust. By the strange third act—which quotes the Sesame Street gang explaining death to Big Bird—we realize that we’re in the presence of a playwright contemplating a father’s death and trying, rather desperately, to help us do the same.—HS